There is no more fraught question in education right now than the question of whether or not to open schools in person during the COVID-19 pandemic. Shut down in-person learning, and opportunity gaps widen, rates of depression climb, and working parents burn out from exhaustion. Keep school buildings open, and they could become super-spreader sites, leading to the death of teachers or children. The risks seem unbearable, whichever you choice you make.

While there is no one “right” answer, research offers at least some clarity to help education leaders make this difficult decision.

Several recent studies have shown that, under certain conditions, it is likely safe to reopen schools in-person. (Schools, of course, never really “closed” at all; learning is still happening, just remotely.) These studies generally agree that rates of COVID-19 infection are relatively low in the community around the school, and the school takes all necessary precautions like requiring masks and social distancing, then in-person learning does not pose a great risk of spreading the virus.

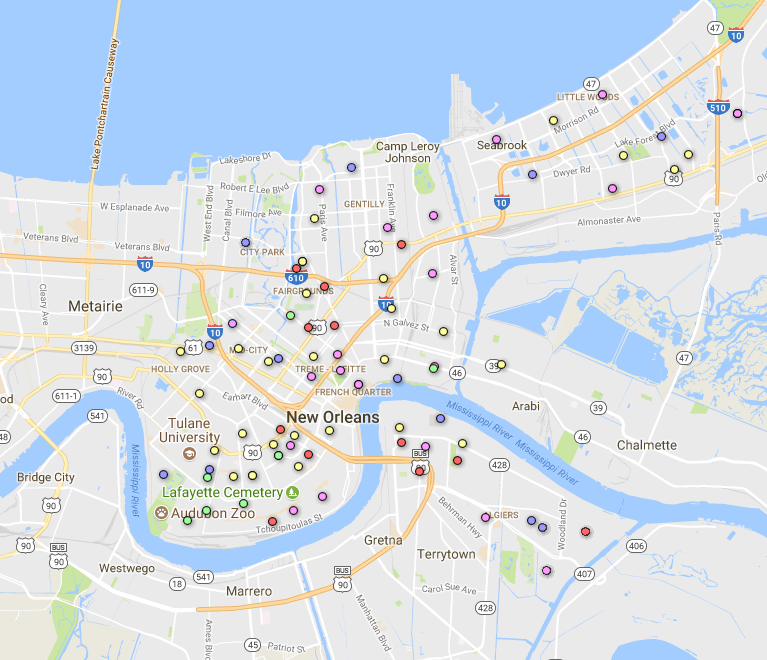

Of course, there’s debate over what exactly “relatively low” means. There’s no magic cut-off point that tells us exactly when it’s safe or not safe to re-open. But research can give us rough guidelines. Researchers at Tulane University, for example, found that “it appears safe to reopen schools in counties where there are fewer than 36 to 44 new COVID-19 county hospitalizations per 100,000 people per week.”

Note that researchers have not proven that it is unsafe to reopen schools in counties above that hospitalization rate. The study is inconclusive on what happens above the range of 36-44 new COVID-19 hospitalizations per week, as different methods of analyzing the data yielded inconsistent results.

Helpfully, the researchers provided a spreadsheet of hospitalization rates in around 2,200 counties across the U.S. The data, which comes from the federal Health and Human Services department, goes back to July 2020 and is updated weekly.

So, can most counties breathe a sigh of relief now? Where is it safer to open schools, and where should district leaders lean more towards remote learning? To find out, I mapped out the latest available data, from the week of January 22-28.

For an interactive version of this map, click here. Zoom in to find your own county.

The situation looks bad in states like California, Arizona, and Florida, where many counties are in the high range of COVID-19 hospitalization rates. Still, most of the map is green, which is a hopeful sign. In those counties, hospitalization rates are low enough that it is most likely safe to send kids back to the classroom.

But that map still doesn’t tell the whole story. The majority of counties may be in the green, but that’s not necessarily where the majority of people in the U.S. live. It could be that hospitalization rates are low in rural, sparsely-populated counties, but high in the big cities where millions of people live.

The following chart shows the share of the population that lives in counties where hospitals are filling up with COVID patients (click here for full screen):

Now, the story looks different. In early September, when the school year was just starting, two-thirds of Americans lived in counties where the spread of COVID-19 was low enough that it was likely safe to send kids off to school. But as of late January, the situation is reversed, and only about one-third of Americans live in such counties.

The researchers have stressed that they are not making recommendations on whether to close or open schools. These numbers are only a guidepost. There are many other factors that school leaders still must take into account, and they must weigh the risks of re-opening with the risks of not re-opening.

Take for example Clark County, Nevada, which saw 88 new COVID hospitalizations for every 100,000 residents in a single week at the end of January. That puts the county far above the limit that’s been confirmed as safe for reopening schools. Yet, as Erica Green masterfully reported in the New York Times, the county has also suffered the wrenching tragedy of losing 18 young people to suicide. Facing a youth mental health crisis, district leaders have chosen to start letting students return to the classroom.

Vegas shows that there are no easy answers to the question of whether it’s safe to open schools. No matter what, there are risks. Research, at least, can help school leaders understand exactly what risks they’re taking.